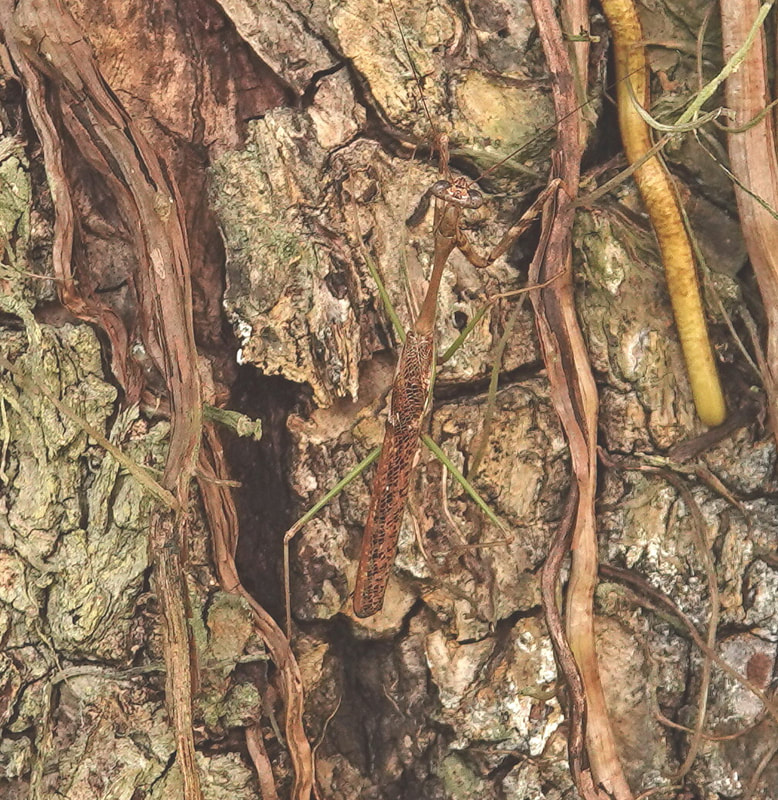

On 14 May 2023, a female Holguinia holguin was observed and photographed by Yosiel while ovipositing on fresh leaves of a climbing grass later identified as Tibisia farcta in the foothills of Alto de Florida, Baracoa, Guantánamo province. The location consisted of a dry serpentine-scrub woodland on the southern slope of a small hill accompanied in this highly diverse and endemic-rich habitat by the endemic skipper Bruner's Skipperling Oarisma bruneri.

The foodplant was previously unknown so well done to Yosiel for unlocking another mystery.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed