|

A source of nectar is as essential a requirement for many butterflies as having the larval foodplants nearby. It's not true for all as there are some that utilize other sources of sugars such as rotten fruit like the Historis and Eunica species and the beautiful Mosaic Colobura dirce amongst others which we have watched on the ground feeding on the fallen fruits of a Mountain Apple Syzygium malaccense (see below). Of those that use flowers for nectar it is usually the females of the species that do this whilst the males get essential minerals and fluids from damp ground. We have most often seen Purple-washed Skipper Panoquina lucas nectaring at flowers close to the ground but the truth is that butterflies will take advantage of nectar wherever that might be so long as their their proboscis is long enough to access it. The interesting photograph at the top was taken by Karen Aguilar Mugica and shows swarms of these skippers using a flowering tree in the Botanic Garden at Habana and described them as being just like bees. She is going to try to find out the name of the tree next time she goes back there. Thank you Karen for letting me use for photograph.

0 Comments

Following my last blog about the epic migration of the Monarch Danaus plexippus in N and Central America which I have never actually witnessed, though I have been told about it by friends, I thought I would talk about another similar butterfly migration that occurs here in Europe though on a smaller scale - that of the Painted Lady Vanessa cardui. This are one of the most widely distributed species of butterfly on the planet and can be found on all continents except Antarctica and Australia. These migrations are now known to start in sub-Saharan Africa and move northwards in spring and summer in generational waves to well within the Arctic Circle. Here in the UK, every ten years or so the migration can be spectacular. The most recent was in 2009. Talk to any butterfly watcher here and they will recount their amazing memories of that year. year it started for us on the morning of 24 May when Lynn and I were visiting a clearing in Bentley Wood in the west of Hampshire looking mainly for Argent and Sable moth. We became aware of things flying past us at great speed. It was only when a third flew past a bit closer and in the same direction, due north, that I realised it was Painted Ladies. We saw about fifteen that day and all were on a mission. But it was the next day when visiting West Down, Chilbolton overlooking the River Test that we realised the scale of what was happening. To be fair it wasn't entirely a surprise as we had heard from friends in Spain a few weeks before saying that there were unprecedented numbers emerging from an earlier wave of immigration heading north out of Africa and that we should be on the look-out. Back on West Down the numbers were impressive so we decided to do timed timed 5 minute counts across a 50m strip of open ground. At 2pm the count was 600 per hour. At 3.50pm count was 840 per hour all flying due north. The only ones we saw were flying at just above ground level though I have to say that we weren't looking for others flying higher up. This was game on - on a scale I had never witnessed before. This wave had all moved through within another two or three days leaving others behind to lay vast quantities of eggs on fields of thistles where these were encountered on their journey north. We now know from research papers that had been published in the previous couple of years that Painted Lady can cover vast distances at high level when the winds are in a favorable direction.. It has been proven using vertical-looking radar that the butterflies do this at altitudes up to 1,200m. You can read more about this in Pete Eeles fabulous book on British and Irish butterflies pictured below. This book took ten years in the making and the standard of photography and the level of detail drawn from personal observation, new science and long-forgotten texts from very talented lepidopterists of past generations make it the best book of its kind anywhere in the world. If you don't have it already you most certainly should. You can read the reviews and purchase it here. Later in 2009 Lynn and I took a short break in in Crete arriving on 13 October and noted small numbers of Painted Lady in the first three days of our stay near Chania on the north-west coast. On 16th October we were at the top of the Topolia Gorge, one of several gorges in western Crete that run in a north/south direction, searching for Cyclamen hederifolium and the diminutive Narcissus serotinus when we became aware of a steady stream of Painted Lady, about 60-80 per hour, flying south along the road towards the gorge at 4pm in the afternoon. The next morning at breakfast in the mountains at Milia increasing numbers were seen, again all heading south, in the early morning sunshine until 10am when it became overcast with drizzle and the migration stopped. The maximum count was 100 in 5 minutes across 50m. A few were seen later in the afternoon flying in light rain but no further migration was noted that day. On 18th further southerly migration was noted all morning and a count at the northern end of the Topolia gorge produced a rate of 400 per hour through the gorge at midday. We met up with friends Henry and Felicity Edmunds on 19th October, our last full day on the island, and they kindly took us out to the slopes of Mount Ida (Psiloritis) in the centre of the island. Whilst enjoying a wonderful picnic amongst the Kermes Oaks, a five minute count across 50m at 2.15pm produced 26 cardui (312 per hour) all heading determinedly due south. By 4.30pm we were down on the south coast at Agios Galini and hundreds of cardui were found nectaring on flowering Tamarisk trees on the beach. Despite the numbers present no visible migration was seen and we speculated that this was due to an unwillingness to set off over the sea that late in the day. By 5pm they had gone to roost among the Tamarisk. We like to think that they made the flight safely across the southern Mediterranean to Africa over the following days, perhaps even the following morning. But the odd thing about all this is that it was not until about this time that people realised that there even was a reverse migration of Painted Lady and most books stated that it didn't happen and wondered why the species hadn't died out. So much great science has been done in recent years. We now know that migrant moths will fly up to several hundred feet at night to test if the winds at altitude are going in the right direction and if they are not they will come back down to ground level and try again the next night. There is no reason to suppose that exactly the same thing happens with butterflies.

The Monarch Danaus plexippus is a fairly scarce resident in Cuba but between October and mid-December the population is boosted by migrants from North America making their southward journey to avoid the harsh winter extremes further north. The beautiful photo above was taken by Gustave Blanco Vale in October 2017 while he was on a bird-banding trip to the extreme western point of the island. he tells me there were about fifteen in the group and they came in to roost in a coconut palm altogether just as it was getting dark. I would love to know whether they then continued on their journey together the next morning and in what direction. Did they go west to Yucatan or somewhere else, or did they stay and feed and roost in the same place the next night? There is so much to be learnt from good fieldwork and observation.

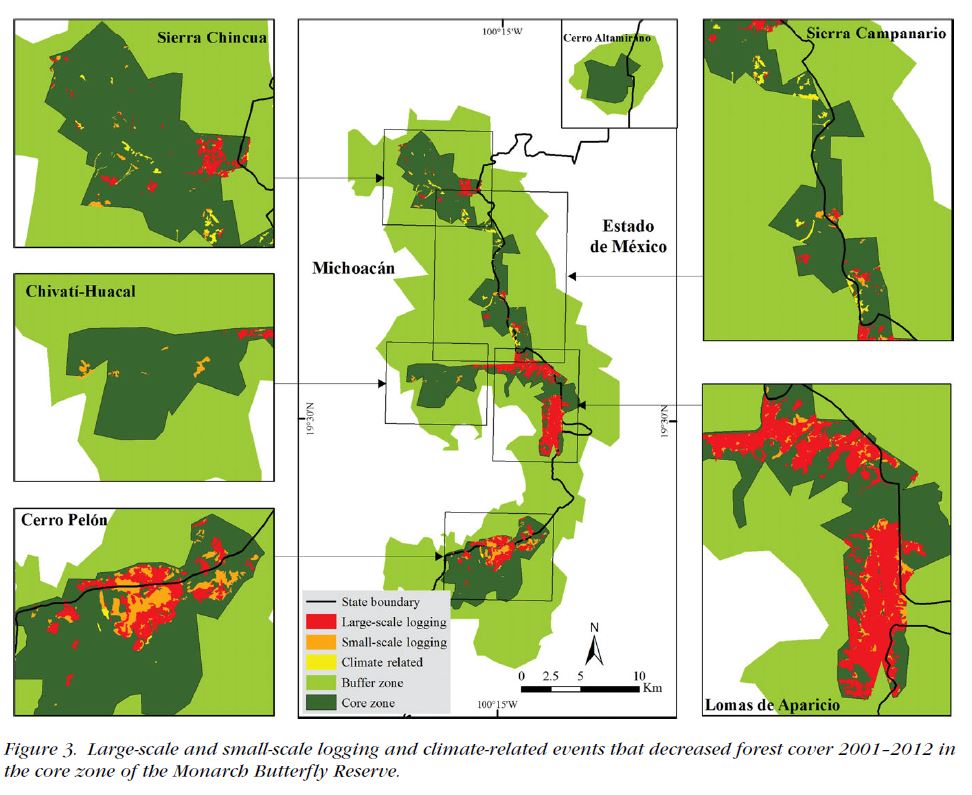

Thank you Gustave for letting me use your photo. Lynn and I had a similar experience in October 2009 but this time it was Painted Lady Vanessa cardui rather than Monarch and I will talk about this in a following blog. In 2002 Cristina Dockx published her PhD dissertation on the migration of Monarch's through Cuba and you can find a link to this on the species page. The Monarch has suffered huge declines across America in recent years due to multiple factors. The numbers at their over-wintering sites in Mexico have dropped from a high of 682 million in 1997 to just 42 million in 2015. So what are the reasons? 1) The greatly increased use of the herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) by farmers in N America has reduced the available foodplant Milkweed on which the caterpillars breed. 2) The use of neonicotinide insecticides (which are designed designed to indiscriminately kill all insects) on farm crops has been shown to be a cause in the decline of bees and other insects. Even ingestion of tiny amounts of contaminated nectar or pollen that are insufficient to directly kill a bee can cause it to sufficiently lose its capacity to navigate such that it cannot find its way back to the hive. And bees are much bulkier that Monarchs which also need their full faculties to be able to navigate their way to their over-wintering sites in the autumn. Research has shown that neonics also play a large part in the catastrophic decline of the Monarch. 3) Climate change/breakdown which raises the winter temperature in the mountains of Mexico where the Monarch's have traditionally overwintered in colossal numbers means that they use more of their fat reserves which are needed to fuel the first stage of their northward migration in the spring. And last but not least- 4) The large-scale and small-scale logging of the forests in Central Mexico were monitored during the period 2001-2012 and the results were absolutely shocking. The murder of two prominent Monarch conservation activists within three days in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in early 2020 is a stark reminder of the extent to which big business will go to line their pockets and trash the planet in the process robbing us one of the greatest spectacles on earth. The Mimic, also known as Danaid Eggfly in some parts of the world, has a widespread distribution across the globe. It originated in Asia but is now found across much of Africa, Central America and the Caribbean. In Cuba it has been known since about 1880 but is quite rare and I haven't heard of anyone seeing one in the last few years until a friend sent me a photo two days ago that he had just taken on his mobile phone near Gibara in the east of the island. When I put the photo on one of the local forums. I was immediately sent a picture of another taken in December at the lighthouse at Punta de Maisi which is the easternmost point of Cuba. It's rather odd that it is seen so rarely when the foodplants that it uses are not uncommon on the island. Larvae have been found in the past so it obviously has bred though the reasons for its current rarity need more study.

Antillean Blue Pseudochrysops bornoi is a globally rare species that has been found on only three islands in the Caribbean - Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico and nowhere else. It has been very rarely seen, let alone photographed in the field and in fact I know of only a few occasions when it has (all in the Dominican Republic) including the above fabulous picture of a pair in cop. Thank you Pedro for allowing me to use it.

In Cuba it was first discovered back in October 1991 and I'm not aware that it has ever been seen or even looked for since until our visit in June 2016 though because it is in an area adjacent to a military zone there is considerable sensitivity in going there and I think it would require express written permission from someone senior in the army. Now that we know that it flies in winter we might try it sometime if we can get permission. Following the publication of the new Butterfly Field Guide (see below) I have just finished updating the names of some of the species here on the website so that they are aligned. Some changes I had been aware of but others were new to me. The changes are: 1) The three Aphrissa species have now been placed back in the genus Phoebis where Bates placed them back in 1935. 2) Caribbean Sailor Dynamine egaea is a junior synonym of Dynamine serina and not the other way round so I have amended. 3) It has now been determined that the single species of Hamadryas in Cuba is in fact in the lineage of Gray Cracker Hamadryas februa and not Hamadryas amphichloe as previously thought. 4) The Chestnut Leafwing Cymatogramma echemus has had quite a few name changes over the years and has now been placed in the genus Cymatogramma rather than Memphis where it had been previously. It used to be considered to be the same species as the Hispaniolan Leafwing C. verticordia which is a bit strange as that has large white spots on the wings, but that was corrected a few years back. In the latest Field Guide Anetia cubana has been called the Florida Leafwing which is not very sensible as it doesn't occur in Florida and is endemic to Cuba, so I have called this Cuban Leafwing. In the Field Guide they have named C. echemus as Cuban Leafwing but as this common name is used for A. cubana I have used Chestnut Leafwing for C. echemus just as other websites like Butterflies and Moths of North America. 5) It had been previously thought that Ephyriades arcas occurred on Cuba as well as E. zephodes but it is now believed from DNA work that has been done (pers. comm.) that the only species of this tricky pair to occur on Cuba and Hispaniola is Ephyriades zephodes. So that brings the total Cuba butterfly list back down to 200 species although it has to be said that a small number of these are of vagrants that have turned up just once or twice a long time ago, even as far back as the 19th century, and for which there is no physical evidence in the form of a specimen. It's fair to say that some of these species would probably not stand up to modern scrutiny for inclusion on a Category A list for a country. I haven't counted up the number of species included in the new Field Guide but that's why it is less that the number detailed here on the website. I have also updated the thumbnail pages and the downloadable species list that you can find here on the website. Enjoy!

Happy New Year everyone and may you all have a wildlife-filled 2021. Swifts are remarkable birds and amongst my favourites. There are 92 species around the world including the Swiftlets and in Cuba there are three resident species - Antillean Palm-Swift, Black Swift and the White-collared Swift. This last is amongst the largest of them all with a wingspan of 450-550mm! In summer they are known to nest in caves and areas close to waterfalls in the mountains in central and eastern Cuba, while in winter they range more widely and can be found at lower elevations. There is an interesting note in the Birds of Cuba (Garrido & Kirkconnell, 2008) that they also nest in hollow Royal Palms. The amazing photo above was taken by Ernesto Reyes Mouriño in the city of Trinidad. Thank you Ernesto for allowing me to use it.

We have only seen them on three occasions in Cuba. All have been during the winter months and all were rather fleeting. Until recently there had been no study of White-collared Swift in Cuba but that changed in 2019 when Dr Rosalina Montes Espin published her doctoral thesis on their Reproductive Biology and Conservation which I have only just come across although I knew she was working on it. It's in Spanish so it will take me a while to read! I also come across this paper regarding the observation of a pair at a waterfall nest site in neighbouring Dominican Republic. |

Welcome to our Blog

Here we will post interesting news about what we and others have seen in Cuba. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed